3-D innovation slashes production time boosts design options and provides owners greater participation in their aircraft build

Surrounded by the stark white walls of an aircraft hangar, the Gulfstream G650, its exterior newly sanded and silky smooth, stands ready for its crowning touch: a painted exterior to distinguish the jet from all others.

Two technicians perched atop a scissor lift carefully unroll masking tape along the aircraft. Every strip determines some aspect of the design, whether graceful curves over an engine cowling or razor-thin separations between stripes along the fuselage.

Taping an exterior once took a crew of technicians anywhere from eight to 12 hours. With a new 3-D software program developed with the help of Gulfstream engineers, the time to prepare an aircraft for painting has been cut in half. With the easier design transfer, the new process also opens the door to more intricate, colorful exteriors.

We are in the customer satisfaction business, so there’s nothing more valuable than being confident in the design process as early on as possible,” says David Minning, engineering group head, of Corporate Product Life Cycle Management, Gulfstream. “With 3-D representation, the customers and the designers can see exactly how the aircraft will look before the first inch of tape has been pulled. We know that we’re doing what everybody wants.”

Also exciting are the possibilities created by giving customers an immediate, full-color 3-D rendering of their aircraft design, not only for the exterior but soon, for interiors as well, which will be accessible for customer review via an iPad app.

“The focus is on giving the customer an easier way to have and make choices,” says Onzetta Roberts, a Gulfstream technical designer. “This allows the customer to become more deeply involved in the design and will allow customers to make changes in real-time.”

The Future Of Painting Airplanes

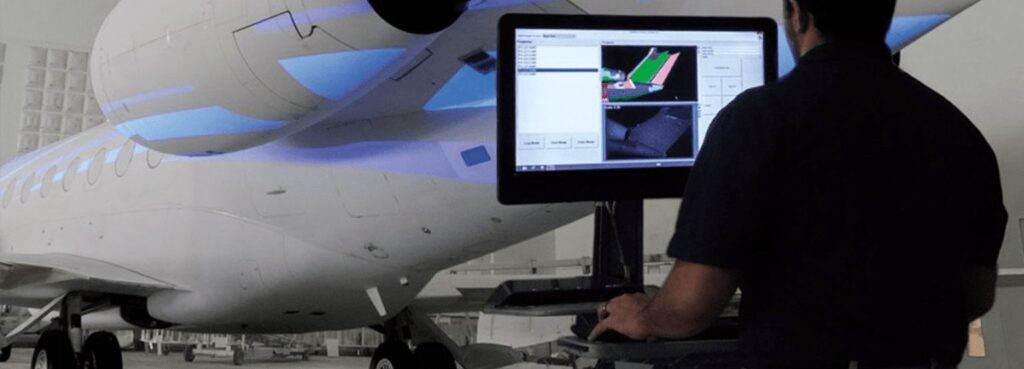

In 2010 Delta Sigma Company introduced ProjectionWorks, a commercial 3-D software program first used to display locations for rivets and other fasteners during aircraft builds. Gulfstream has incorporated that technology in its production lines, but engineers saw possibilities for other Gulfstream applications, including painting exteriors.

Gulfstream had previously explored laser-projected paint designs but the pulsating light wasn’t conducive to the work. This time, with more capable technology, the Life Cycle team developed software that creates and projects the design in 3-D, eliminating the 2-D design phase.

Before 3-D, mapping an aircraft’s exterior design had remained almost unchanged for 40 years. In the traditional method, technicians used a 2-D schematic as a reference as they plotted the design along the aircraft.

A laser level ensured straight lines, which were then taped. Curved lines were formed by matching the design to specific points on the aircraft. A curve might begin about three inches from a nacelle, then sweep toward the T-tail. The more complex the design, the greater the possibility it might deviate from the drawing. Even with newer computer-assisted design, the most practiced eye had to interpret differences between the flat 2-D version and how it would lay over the aircraft surfaces.

“Ten people can look at a flat drawing, and those same 10 people can have a different interpretation of what that means and how it’s supposed to look on the plane,” says Roger Richardson, CEO, and director of business development for Delta Sigma. “I like to say the augmented reality projection software creates is like seeing into the future. On a 3-D render, you do not need one ounce of paint or any taping before the customer can see the full-size aircraft design as it will look when the paintwork is complete.”

The 3-D paint software didn’t come without some engineering finesse. Simply projecting a 2-D image onto an aircraft won’t work. The curved surface will distort the image, turning a circle, for example, into an oval.

“That’s the magic,” Minning says. “The software defines how the image needs to be shaped to display correctly on a three-dimensional surface.”

Once a design is customer-approved, high-resolution projectors at various angles shoot the design onto the aircraft surfaces. From 20 feet away, the image appears as one solid pattern. Within a few inches of the aircraft, the image pixelates, which allows technicians to tape precisely pixel by pixel.

“With 3-D representation, the customers and the designers can see exactly how the aircraft will look before the first inch of tape has been pulled.“

The Benefits Of Mixed Reality For Painting Airplanes

One recent exterior completion demonstrates how easily design changes can be made. The customer was in the Savannah, Georgia, paint hangar when the approved design was projected onto the G650. Although lines running along the fuselage reflected the 2-D technical drawing, on the aircraft, they didn’t have as much space between the lines as the customer had anticipated. Technicians wanted an expert to adjust the design, so they contacted Nick DelCore, a Life Cycle engineer who was instrumental in developing the 3-D process. He was visiting family in Ohio but accessed the system remotely to adjust the drawing.

“Minutes later, when we called up the new image in the computer and projected it on the aircraft, the customer said, ‘That’s perfect. That’s what I wanted to see.’” Minning says. “That moment was validation of three years of work.”

Publications

This article and its contents are syndicated from Nonstop Gulfstream written by Lesley Conn and photographed by Stephanie Lipscomb.